Structural wood beams are fundamental components in construction. They provide crucial building support for framing, roof support, and floor joists in residential buildings. You will encounter various types of wood beams, including solid sawn, glulam, and engineered structural wood beams. Understanding these different types of wood beams is vital for any construction projects. Choosing the right types of beams ensures structural integrity, saves money, and enhances visual appeal.

Key Takeaways

Solid wood beams come from tree trunks. They are strong and natural. Builders use them in many homes.

Engineered wood beams are modern. They combine wood pieces with glue. This makes them stronger and more even than solid wood.

Glulam, LVL, and PSL are types of engineered beams. They offer different strengths and uses for building.

Special beams like box beams and flitch beams solve unique building problems. They can be lighter or stronger.

Choosing the right beam is important. Consider weight, length, and how it looks. Always ask an expert for big projects.

Solid Wood Beams

Solid wood beams are a cornerstone of traditional building. You find them in many structures. These beams come directly from tree trunks. Workers cut them into specific sizes. This process gives you a strong, natural building material.

Solid Sawn Lumber

Solid sawn lumber is the most common type of solid wood beam. You get it by sawing logs into rectangular shapes. This lumber is then dried and graded. It comes in various sizes. You often see it in residential construction.

Common softwood species are popular for solid sawn lumber. These woods are easy to work with and widely available.

Spruce: Builders primarily use spruce in residential construction. You see it in single-family houses and for the exterior covering of multi-family buildings.

Pine (Yellow Pine or Western Pine): This wood is common in residential framing. Some people call it construction pine. You find it at most lumberyards.

Fir (Douglas Fir or Oregon Pine): This wood has excellent weathering qualities. You often use it on the exterior of homes. Framing lumber widths are available in exterior grades.

The strength of solid sawn lumber varies by species. Wood generally has Modulus of Elasticity (MOE) values from 800,000 to 2,500,000 psi. Modulus of Rupture (MOR) values range from 5,000 to 15,000 psi. These values depend on the wood species. MOE measures stiffness. MOR shows the maximum strength a beam can resist.

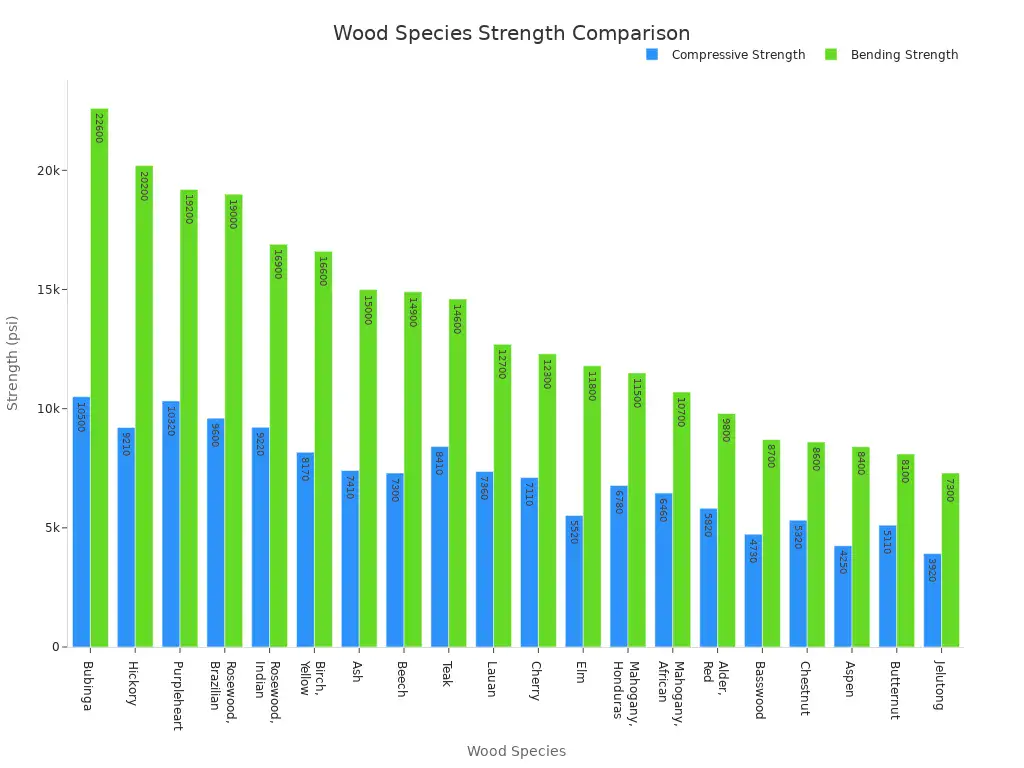

You can understand wood strength through different measures:

Compressive strength: This measures the load a wood species can withstand parallel to the grain before buckling. It is in pounds per square inch (psi).

Bending strength (Modulus of Rupture): This shows the load the wood can withstand perpendicular to the grain. It is also in psi.

Stiffness (Modulus of Elasticity – MOE): This tells you how much the wood will deflect under a perpendicular load. It is in millions of pounds per square inch (Mpsi).

Hardness: This reveals the resistance of the wood’s surface to scratches and dents. It is in pounds (lb).

Here is a look at the strength properties of various wood species:

Wood Species | Compressive Strength (psi) | Bending Strength (psi) | Stiffness (Mpsi) | Hardness (lb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bubinga | 10,500 | 22,600 | 2.48 | 2,690 |

Jelutong | 3,920 | 7,300 | 1.18 | 390 |

Lauan | 7,360 | 12,700 | 1.77 | 780 |

Mahogany, African | 6,460 | 10,700 | 1.40 | 830 |

Mahogany, Honduras | 6,780 | 11,500 | 1.50 | 800 |

Purpleheart | 10,320 | 19,200 | 2.27 | 1,860 |

Rosewood, Brazilian | 9,600 | 19,000 | 1.88 | 2,720 |

Rosewood, Indian | 9,220 | 16,900 | 1.78 | 3,170 |

Teak | 8,410 | 14,600 | 1.55 | 1,000 |

Alder, Red | 5,820 | 9,800 | 1.38 | 590 |

Ash | 7,410 | 15,000 | 1.74 | 1,320 |

Aspen | 4,250 | 8,400 | 1.18 | 350 |

Basswood | 4,730 | 8,700 | 1.46 | 410 |

Beech | 7,300 | 14,900 | 1.72 | 1,300 |

Birch, Yellow | 8,170 | 16,600 | 2.01 | 1,260 |

Butternut | 5,110 | 8,100 | 1.18 | 490 |

Cherry | 7,110 | 12,300 | 1.49 | 950 |

Chestnut | 5,320 | 8,600 | 1.23 | 540 |

Elm | 5,520 | 11,800 | 1.34 | 830 |

Hickory | 9,210 | 20,200 | 2.16 | † |

You also find solid sawn lumber graded into strength classes. These classes help you choose the right beam for your project.

Strength class C14: You use this for wall studs in load-bearing internal and external walls. It works when deformation requirements are less strict. It allows individual knots up to half the width and full thickness. Top ruptures up to three-quarters of the width are also permitted. Firm rot is allowed in narrow strips and bands.

Strength class C18: This class suits load-bearing structures that do not need high strength. Or, you use it where larger dimensions or shorter lengths are possible. It permits individual knots up to two-fifths of the width and four-fifths of the thickness. Small amounts of firm rot are acceptable.

Strength class C24: You use this in load-bearing structures needing high strength. Examples include roof trusses and floor systems. It permits individual knots up to one-quarter of the width and half of the thickness. Top ruptures are not allowed in the outer one-quarter of the width.

Strength class C30: This class is ideal for load-bearing structures needing high strength. You use it when you cannot use large dimensions. It permits individual knots up to one-sixth of the width and one-third of the thickness.

Strength class C35: This class suits load-bearing structures needing extra high strength. You use it when you cannot use large dimensions. Only mechanical grading can classify this wood.

Applications of Solid Beams

Solid wood beams have many traditional applications in construction. You often see them in homes and light commercial buildings. These beams provide reliable support.

You use solid sawn lumber for:

Residential framing.

Short to medium spans in homes.

Outdoor structures (if pressure-treated).

You also find these solid wood beams in roofing projects:

Residential roofing projects.

Light commercial roofing projects.

The versatility of solid wood beams makes them a popular choice in timber construction. They offer a natural look and proven strength for many building needs.

Engineered Wood Beams

You will find engineered wood beams are a modern solution in construction. Manufacturers create these beams by bonding together wood fibers, veneers, or strands with adhesives. This process makes them stronger and more consistent than solid lumber. These engineered wood products offer many advantages. They provide greater strength, more consistency, and allow for custom shapes. Understanding these types of wood members helps you choose the best material for your project.

Glued Laminated Timber (Glulam)

Glued Laminated Timber, or Glulam, is a popular choice for engineered wood beams. You make Glulam by bonding together multiple layers of wood laminations with durable adhesives. This process creates large, strong beams.

Here is how manufacturers make Glulam beams:

Drying and Grading Lumber: First, they check the lumber for moisture. It needs to be between 8-14%. They redry it if needed. Workers trim knots and group lumber by grade.

Joining Lumber: To make longer pieces, they join lumber ends. They typically use finger joints. A strong resin, like melamine formaldehyde or PF resin, is applied. It cures under pressure.

Gluing Layers: After planing for smooth surfaces, they spread resin onto the lumber. Common resins include phenol-resorcinol-formaldehyde, PF, or melamine-urea-formaldehyde. They stack the layers in a clamping bed for straight beams or a curved form for curved beams. Then, they press them together.

Curing: The beams cure at room temperature for 5-16 hours. RF curing can speed up this process.

Finishing and Fabrication: Workers sand or plane off excess resin. They may sand further, round corners, or fill knot holes. They also apply sealers or primers based on how the beam should look.

Glulam offers impressive benefits. It is less likely to shake, check, or warp. This makes it more stable than traditional timber. Glulam has a higher strength-to-weight ratio than steel. This means it can support heavy loads over long spans efficiently. For example, Douglas fir glulam beams can reach a bending strength of up to 2,400 psi. Their modulus of elasticity can be up to 1.8 million psi. The laminating process distributes natural imperfections. This ensures consistent performance. An 8.75-inch-wide glulam beam typically changes less than a quarter-inch in width when humidity changes. This is due to the bonded layers distributing stresses.

You can get Glulam in many custom shapes. These include straight, curved, pitched, radial, and even Tudor arches. You also find Glulam in varying wood grades, depending on its intended use and appearance.

Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL)

Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) is another type of engineered wood beams. It is one of the strongest wood-based construction materials for its density. You make LVL by bonding thin wood veneers together with adhesives. All veneers have their grain aligned in the same direction. This makes LVL very strong, especially for beams.

Here is how manufacturers produce laminated veneer lumber:

Veneer Production: They create thin veneer sheets, usually 2.5 mm to 4.8 mm thick, from logs. They use a rotary peeling technique. A pressure bar ensures uniform thickness.

Veneer Drying: They clip continuous veneer ribbons to specific widths. Then, they dry them in jet tube dryers with hot air. This reduces moisture content to a target level, like 8-10%.

Defect Elimination and Assembly: Workers remove defects from individual veneers. They distribute remaining defects randomly during assembly. This ensures uniform strength. Unlike plywood, LVL veneers are assembled with their grain aligned longitudinally.

Adhesive Application and Pressing: They apply an exterior adhesive, usually phenol formaldehyde, to each veneer sheet. Then, they assemble these layers and press them at high temperatures (250 to 450 degrees Fahrenheit).

Billet Manufacturing: They produce large billets, up to 6 feet wide. These can have a maximum shipping length of 80 feet.

Laminated veneer lumber offers excellent dimensional strength. It has a great weight-strength ratio. It is stronger relative to its weight compared to solid materials. Its homogeneous quality and even defect distribution make its mechanical properties highly predictable. You can use laminated veneer lumber in various dimensions and shapes. It is not limited by log size. This makes it very versatile.

You often use LVL for beams, headers, and rim boards. Its strength and rigidity make it ideal for supporting heavy loads in floor and roof systems. You also use LVL as rim boards and rim joists in residential and commercial construction. These parts frame the floor system and provide lateral support.

Parallel Strand Lumber (PSL)

Parallel Strand Lumber (PSL) is a type of structural composite lumber. You make PSL from long, thin wood strands. These strands are laid in parallel and bonded together with strong adhesives. This process creates a very dense and strong product.

Here is how manufacturers make PSL:

They clip wood elements into strands. These strands are about ¼ inch wide and at least 300 times longer than their width.

They combine these strands with exterior waterproofing adhesives.

The adhesive-coated strands form a large billet.

They press the billet together.

Finally, they cure the pressed billet using microwave radiation.

In Canada, PSL primarily uses Douglas-fir. Other common woods include beech, pine, and conifer. PSL comes in different grades, such as 1.8E, 2.0E, and 2.2E. You typically use 1.8E Parallam PSL for columns. It offers high vertical load capacity. You can also use it for beams and headers. The 2.0E/2.2E Parallam PSL is a beam product. It has larger depths, up to 18 inches. This makes it suitable for long spans and heavy loads. You can also use it as a column when you need high load capacity. Solid sections of Parallam PSL offer greater lateral stability. This can reduce the need for compression edge bracing.

Laminated Strand Lumber (LSL)

Laminated Strand Lumber (LSL) is another form of structural composite lumber. You make LSL from flaked wood strands. These strands are layered in specific orientations and bonded with adhesives. This differs from PSL, which uses longer veneer strands laid strictly parallel.

LSL can bear heavy loads. It resists warping or shrinking. It offers consistent quality and dimensions. This makes it different from natural wood. LSL is also environmentally friendly. Manufacturers make it from fast-growing, smaller trees.

LSL is generally not as strong as PSL. However, it is cost-effective and naturally straight. This makes it suitable for modern homes, kitchens, and bathrooms. You most commonly use LSL as rim board, studs, and short headers. TimberStrand LSL is used for building tall, strong, stable, and straight walls. It is available in lengths up to 30 feet. You can use it for studs, sill plates, and headers. LSL is also suitable for headers and beams, especially when you need long spans. You can integrate it into floor systems to create a stable base.

Oriented Strand Lumber (OSL)

Oriented Strand Lumber (OSL) is also a type of structural composite lumber. It is made from flaked wood strands. A key part of OSL’s manufacturing is that these wood strands are arranged in a parallel formation.

The main parts of OSL are flaked wood strands and an adhesive. The strands have a length-to-thickness ratio of about 75. Manufacturers orient these strands. Then, they combine them with the adhesive. They form them into a large mat or billet. Finally, they press this billet.

Specialized Types of Beams and Structural Elements

You will find many specialized beams and structural elements in construction. These components solve unique building challenges. They offer specific benefits for strength, aesthetics, or space.

Box Beams

Box beams, also known as faux beams or hollow timber, mimic the look of solid timber. They are much lighter. This makes them easier to install. You can construct them from wood or steel. For wood, you often use materials like Englemann Spruce, #2 Grade, with a thickness of 11/16 inches. You can get them in lengths from 4 feet to 15 feet 6 inches as a single board. You can make them infinitely long with joints. They can be up to 10½ inches wide and high as a single board, or 21 inches with a glue seam. Common joints include Lap, Lock, Butt, and Assembled Scarf.

Box beams are very durable, even when hollow. Their box shape provides a secure platform. It balances, distributes, and supports a structure’s weight. They are lightweight, making installation easier. You can customize their size for different designs. Their hollow interior can hide wires, cables, or pipes. This offers a practical solution for concealing unattractive elements.

Flitch Beams

A flitch beam is a composite structural element. You use it in wood-frame construction. It combines wood and steel. You typically sandwich a vertical steel plate between two wooden beams. Bolts secure these three layers together. This creates a steel flitch beam. You can add more alternating layers of wood and steel for extra strength. The metal plates inside are called flitch plates.

Flitch beams offer enhanced structural load strength. They do not increase the overall beam size. This allows for greater load-bearing capacity. You can support heavier loads or longer spans. The steel plates also increase stability. They distribute loads effectively. You often choose flitch beams for tighter spaces. They are useful in old construction restoration. They help create large, open spaces. You also use them in roof support structures, especially where heavy snowfall occurs.

Wood I-Joists

Wood I-joists get their name from their “I” shape. They have two horizontal parts called flanges. A vertical part called a web connects them. Manufacturers make flanges from solid sawn lumber or structural composite lumber (SCL), like LVL. Webs typically consist of high-strength oriented strand board (OSB).

I-joists offer remarkable strength and load-bearing capacity. They use fewer natural resources. They span longer distances than solid wood beams of the same size. This makes them ideal for open floor plans. They reduce the need for supporting columns. I-joists are lighter and easier to handle than traditional lumber. They are less likely to twist, split, or bow. This ensures consistent performance.

Hip Beams

Hip beams are crucial in hipped roof structures. They support the roof’s weight. Hip rafters receive loads from other framing members called jack rafters. Engineers design hip rafters as beams. This is especially true when the roof slope is below 3:12. Hip support columns help support hip members at the ridge. This ensures a continuous load path down to the foundation.

Joists, Trusses, and Braces

You will find joists, trusses, and braces play distinct roles in construction.

Joists support floors and ceilings. They transfer weight to walls or beams. They provide a stable base for flooring and drywall.

Trusses are triangular frameworks. They efficiently distribute loads. The top chord experiences compression. The bottom chord is in tension when a load applies.

Braces reinforce structural systems. Cross-bracing and solid blocking strengthen floor joist systems. They distribute floor loads and prevent twisting. Strongback bracing enhances stiffness for roof trusses and I-joists.

Beam Selection Guide

Choosing the right beam for your building is very important. You need to pick the correct type for your construction projects. This guide helps you understand how to make good choices.

Key Selection Factors

You must consider several things when you pick a beam. First, think about the weight the beam will hold. This includes permanent parts of the building, like roofs and floors. These are called dead loads. It also includes things that move, like people and furniture. These are live loads. Snow on the roof creates snow loads. Wind pushing against the building creates wind loads. You must consider all these loads.

Load and Span Calculations

You need to calculate how much weight a beam can hold and how far it can stretch.

Beam Volume per Meter Length: You find this by multiplying the beam’s width, depth, and length.

Beam Load per Meter Length: You get this by multiplying the beam’s volume by the material’s density.

Total Beam Length per Floor: You calculate this by dividing the floor area by the beam spacing.

Total Beam Load for One Floor: You find this by multiplying the total beam length by the beam load per meter.

Total Beam Load for Multiple Floors: You multiply the single-floor load by the number of floors.

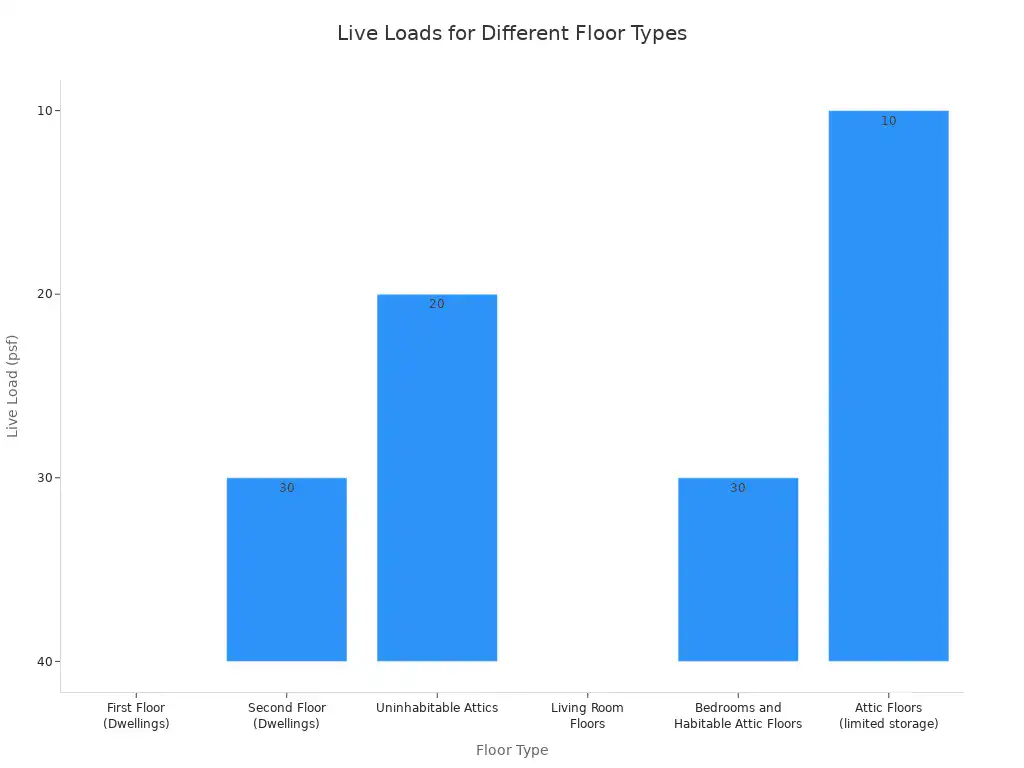

You also need to know about live loads for different floor types.

Category | Live Load (psf) | Dead Load | Deflection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|

First Floor (Dwellings) | 40 | * | L/240 (unplastered) |

Second Floor (Dwellings) | 30 | * | L/240 (unplastered) |

Uninhabitable Attics | 20 | * | L/180 (unplastered) |

Plastered Construction | N/A | N/A | L/360 |

Living Room Floors | 40 | N/A | L/360 |

Bedrooms and Habitable Attic Floors | 30 | N/A | L/360 |

Attic Floors (limited storage) | 10 | N/A | L/240 |

*Dead load values are typically found in the code book appendix or determined by summing weights of permanently installed materials. Deflection limits are based on live loads.

Beam calculations look at strength and stiffness. Strength means the beam will not break. Stiffness means it will not bend too much. Building codes tell you the maximum amount a beam can bend. You can find these rules in code books and span tables.

Aesthetic and Environmental Considerations

The look of your wood beam matters, especially if people will see it.

Grain Patterns: These can be open, like oak, or subtle, like maple. They change how the wood looks and feels.

Color Variations: Different woods have different colors. Maple is light, and cherry has rich red tones.

Texture: Wood can feel smooth or rough. This affects how it looks and how you touch it.

Finishing Properties: Finishes make wood look better and protect it. They can make the grain more visible or change the color.

You also need to think about the environment. Buildings create a lot of greenhouse gases. Using mass timber, like glulam, can lower these emissions. Always check for certifications like FSC or SFI. These show the wood comes from forests managed in a good way. This helps ensure the durability of our planet’s resources.

When to Consult an Expert

You should always talk to an expert for complex structural decisions. They understand all the rules and calculations. They help you choose the safest and best beam for your project.

You have explored many types of structural wood beams. These include solid sawn, glulam, and other engineered types of wood beams. Each offers unique properties for your projects. Understanding these different types of wood beams is crucial. It ensures safe, durability, and efficient construction. You must select the correct structural wood beams based on project needs and building codes. For complex decisions, always consult an expert.

FAQ

What is the main difference between solid sawn and engineered wood beams?

Solid sawn beams come directly from a single log. You cut them into shape. Engineered wood beams use wood fibers, veneers, or strands. Manufacturers bond these pieces together with adhesives. This process creates stronger, more consistent products.

What are Glulam beams?

Glulam beams are engineered wood products. You make them by bonding multiple layers of wood laminations. Durable adhesives hold these layers together. This process creates large, strong beams. You can get them in many custom shapes.

What is a flitch beam?

A flitch beam is a composite structural element. It combines wood and steel. You sandwich a vertical steel plate between two wooden beams. Bolts secure these layers. This design offers enhanced strength without increasing beam size.

What are wood I-joists?

Wood I-joists are engineered beams shaped like the letter “I”. They have horizontal flanges and a vertical web. Flanges are often solid lumber or LVL. Webs typically use OSB. I-joists are strong, lightweight, and span long distances.